Anomie: Why It Keeps Failing

When Norms Remain Visible but No Longer Bind

Most people do not begin by saying, “I am living through an anomic condition.” They begin with something smaller, more ordinary, and more difficult to argue with: a sense that modern interaction has become strangely expensive. Not expensive in money, at least not primarily. Expensive in attention. Expensive in interpretation. Expensive in the low-grade vigilance required to move through ordinary exchanges—work, friendship, institutions, romance—without the assurance that words will hold, timing will mean anything consistent, or commitments will remain stable long enough to be trusted. One is not necessarily surrounded by hostility. Often the atmosphere is polite, even warm. Yet the outcomes remain oddly unreliable. The question that naturally follows is not “Who is bad?” but “Why does it keep failing even when no one is trying to fail?”

Anomie is not a lament for the decay of virtue. It is not a nostalgic argument for the restoration of prior customs. It is a term of art, introduced because the ordinary moral vocabularies—corruption, vice, selfishness—misdescribe the phenomenon it was meant to capture.

Anomie names a particular failure of coordination: a condition in which norms remain culturally visible and continually invoked, yet no longer bind behavior reliably across time.

This distinction matters. The anomic environment is not normless. On the contrary, it is frequently saturated with normative speech: intentions, boundaries, values, and assurances. What changes is not the presence of rules, but the force with which rules constrain action and close outcomes. The grammar persists; the enforcement deteriorates.

Where binding fails, settlement becomes optional. Where settlement becomes optional, interpretation expands. The burden of regulation migrates from structure to cognition. A society can therefore maintain considerable surface order—participation, politeness, sincerity—while losing the capacity to produce predictable coordination.

That is anomie.

The concept enters sociology at the end of the nineteenth century amid industrialization, urbanization, and accelerated economic transformation. Traditional mechanisms of regulation—religious authority, inherited roles, local custom, embedded reputation—were losing their capacity to delimit expectation and discipline desire. New institutions were proliferating, but had not yet stabilized into binding forms.

Crucially, social life did not dissolve. Individuals continued to work, trade, marry, compete, and participate. What weakened was something more subtle and more decisive: the ability of norms to make conduct predictable, to render obligations enforceable, and to close the future.

Durkheim introduced anomie to name this problem precisely because moral description mislocated its cause. The instability did not originate primarily in willful defiance of norms. It originated in the declining capacity of norms to regulate outcomes.

Rules remained present. But they no longer held.

Durkheim’s analysis is frequently reduced to a psychological generality: rapid change produces confusion. That reduction misses the functional core.

Durkheim’s claim was structural: anomie is a condition in which the mechanisms that ordinarily calibrate aspiration weaken. Desire becomes unbounded not because individuals become uniquely acquisitive, but because the environment no longer specifies what counts as sufficiency, limit, or completion.

This is why Durkheim observed anomie not only in downturns but also in expansion. Prosperity loosens the relationship between effort and settlement. If success ceases to close striving—if gain does not stabilize expectation—then the system fails to regulate ambition. Individuals remain active, but their internal constraints lose external support.

Anomie, in this sense, is not moral chaos. It is miscalibration: a weakening of the social devices that render “enough” legible and enforceable.

Merton sharpened the analysis by relocating the anomic condition into the relationship between culturally prescribed goals and the institutionally available means of achieving them. His contribution was to demonstrate that anomie could be understood not as cultural vacancy but as structural strain: a mismatch between what a society encourages people to pursue and what it reliably permits them to do.

From this follows Merton’s familiar typology—conformity, innovation, ritualism, retreatism, rebellion—not as a moral catalogue, but as rational adaptations to systemic incoherence. Individuals do not behave “deviantly” because they are defective. They behave differently because they are responding to the same contradiction under different constraints.

Strain theory thus permitted sociology to describe patterned outcomes without resorting to individualized blame. The question became not “Why are people immoral?” but “What does this structure select for?”

However, Merton’s framework retains an assumption that late-modern conditions increasingly erode:

that goals remain explicit enough to function as shared reference points.

One can only conform to a goal that is socially identifiable. One can only innovate around a goal whose contours are stable. One can only ritualize means if the goal retains cultural authority.

The contemporary environment introduces a further mutation: the deterioration not merely of means, but of goal legibility itself.

At this point a third reference becomes unavoidable, not because it is clever, but because it is descriptively accurate.

In the late twentieth century, modern societies did not merely become faster, freer, and more pluralistic. They became risk-managed. And risk management did not remain confined to insurance tables or interest rates. It became a general logic—one that quietly migrated into ordinary life.

Here a different Merton is useful: Robert C. Merton, whose work on option pricing and financial derivatives formalized something that looks, at first glance, purely technical. Yet its sociological meaning is unmistakable.

A derivative is not a new asset. It is a new way of relating to an asset. It does not create value from nothing. It reorganizes exposure—unbundling risk, redistributing it, pricing it, and making it movable. In derivatives markets, actors do not primarily seek outcomes in the underlying asset itself; they seek positions that control payoff under uncertainty.

This is the important move: the point of the derivative is not commitment.

The point is optionality.

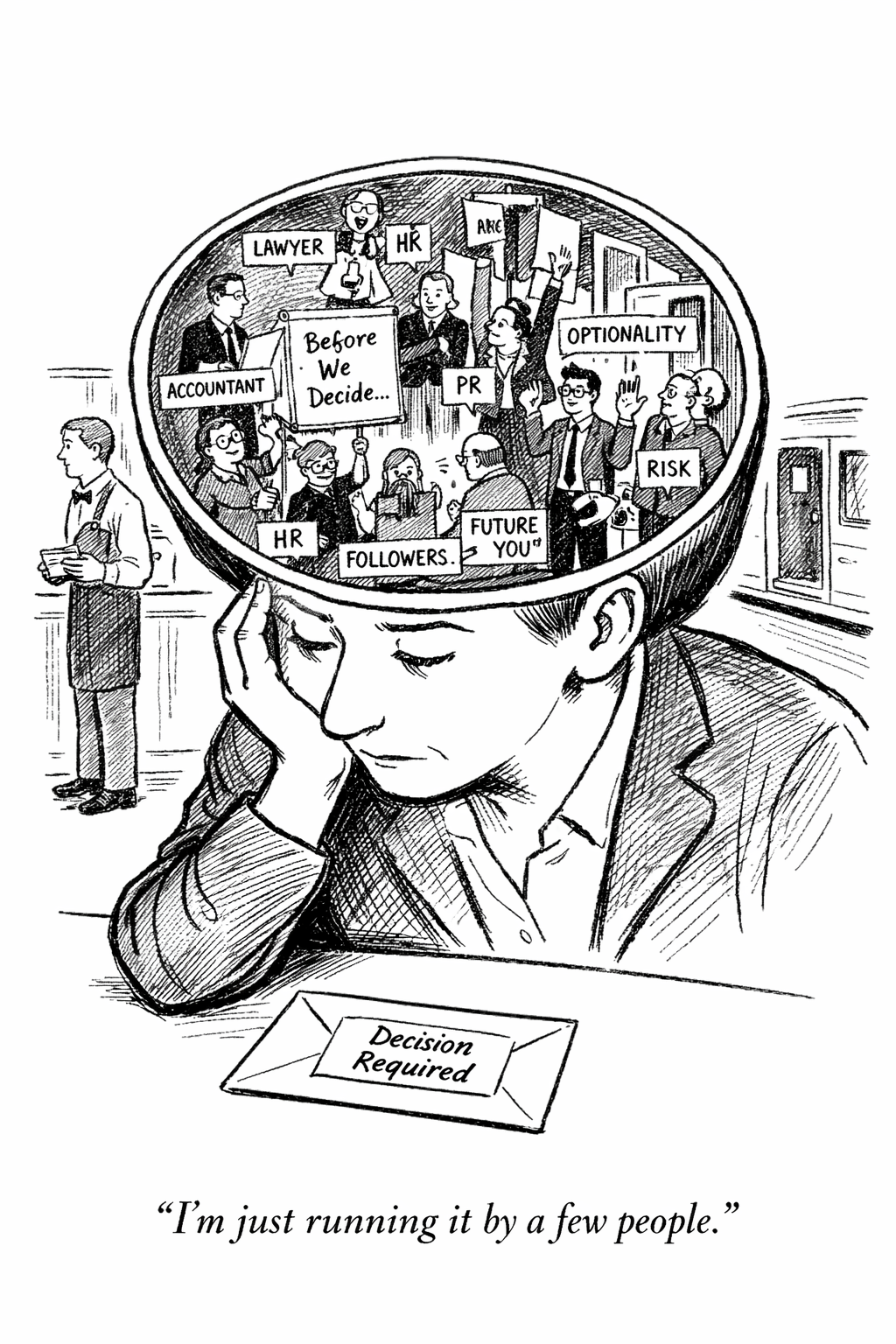

When this same logic migrates out of finance and into everyday trust interaction, we can name it plainly: Interpersonal Engineering—the use of timing, ambiguity, and reversible commitment to improve one’s personal risk–reward profile while externalizing coordination cost onto others. In finance, this is called sophistication. In intimacy, it looks like “just seeing how it feels.” Structurally, it is the same move: participation without settlement.

You can profit from motion without owning the thing.

You can gain upside while capping downside.

You can remain involved while preserving exit.

In finance, this is rational. It is often stabilizing. It permits investment and innovation under uncertainty. It is, in the best sense, engineering: the quantification of risk so that economic activity can proceed without catastrophic fragility.

But the same logic becomes destructive when it migrates into domains that depend on binding in order to function—friendship, intimacy, authority, obligation, and trust.

The contemporary world increasingly treats interpersonal interaction as if it should be risk-managed in the same way financial exposure is risk-managed: participation without settlement, attention without obligation, warmth without closure, connection without consequence. One remains “in the market” while avoiding the costs once associated with choosing.

This is not simply avoidance. It is not merely emotional immaturity. It is an institutional style.

It is what happens when the system rewards the ability to maintain engagement at low personal exposure. When this occurs, people learn to behave like portfolio managers of their social lives: diversifying attention, hedging commitment, avoiding concentration risk, preserving optionality, and treating binding as an unacceptable vulnerability.

In other words, what the derivative did to financial assets—separating participation from ownership—modern systems now do to trust interaction—separating connection from obligation.

The consequence is not a world without norms. It is a world in which norms become increasingly soft, increasingly reversible, increasingly non-binding—because binding itself is treated as excess exposure.

This creates a paradox that Durkheim and RKM did not have to confront in quite this form:

A society can become highly expressive, highly choice-rich, and highly communicative while becoming less capable of producing durable coordination.

The system appears more humane. The outcomes become less stable.

In this sense, “anomie” is no longer merely a disturbance of rules or an absence of shared meaning. It becomes something closer to a generalized risk-management regime—one that continuously permits interaction while refusing to permit settlement.

And once settlement is no longer structurally enforced, interpretation expands, vigilance becomes permanent, and exhaustion becomes rational.

This is the hinge where Anomics begins: not as a critique of freedom, nor as an argument for nostalgia, but as an attempt to describe what happens when the logic of hedging escapes finance and becomes the operating system of modern social life.

The contemporary environment does not abolish norms. It multiplies them. Yet it simultaneously weakens their binding force by rendering them reversible, negotiable, and temporally non-committal.

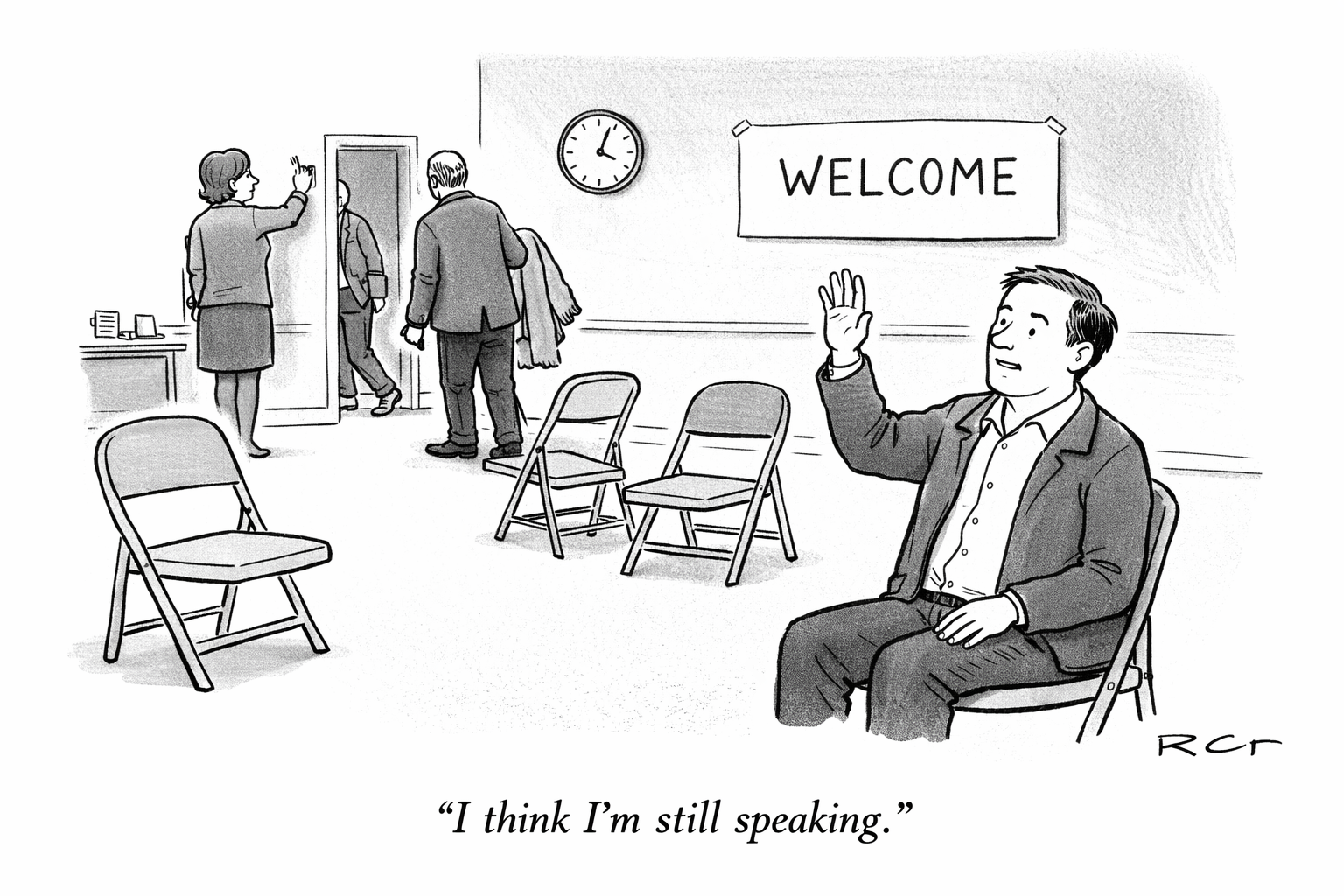

Norms increasingly function as signals rather than constraints.

Institutions and individuals now produce continual normative speech—preferences, intentions, boundaries, values—while hesitating to enforce closure. Explanation replaces consequence. Interpretation replaces decision. Time passes without settlement.

The result is a distinct form of coordination failure: participation continues without coherence. The system remains active but becomes unreliable. One cannot infer trajectory from speech, because speech is no longer obligated to survive time.

This is why the central subjective report of late-modern interaction is not tragedy but fatigue. Individuals are not exhausted because they feel too much. They are exhausted because they are required to carry privately the work formerly carried by structure.

Under anomie, the burden does not disappear. It relocates.

My work begins with the proposition that anomie is no longer an episodic disturbance or a localized condition. It is becoming the operating system of modern trust interaction.

Dating provides a vivid case because the consequences of coordination failure are immediate and intimate. But the mechanism is not confined to dating. The same pattern appears across domains that require binding for trust to function:

- institutions and legitimacy

- medicine and compliance

- markets and contracts

- work and authority

- education and credentialing

- friendships and social obligation

- family systems and role expectations

The overarching diagnosis is structural:

the modern environment is characterized by binding failure.

The central mechanism is not ideological conflict. It is coordination collapse following the weakening of temporal obligation. We increasingly behave as though meaning is something one expresses rather than something one must continue to enact.

And here the Mertonian emphasis becomes useful because it prevents two common errors at once. The first is the moral error: treating coordination failure as proof of individual defect. The second is the sentimental error: treating it as a failure of empathy, communication skill, or sincerity. Those variables matter, but they do not govern the system.

What governs the system is binding.

And what we have produced, with remarkable efficiency, is an environment in which binding is treated as optional while participation remains compulsory for anyone who wants ordinary human outcomes—trust, cooperation, intimacy, legitimacy, continuity.

At this point, it is worth making a distinction that is often blurred in public discourse.

There is a difference between a latent function and an unanticipated consequence.

Latent functions are effects that are built into the operation of a system, whether acknowledged or not; they are functional in the sense that they sustain the system’s ongoing pattern. Unanticipated consequences, by contrast, are precisely what they sound like: outcomes produced by purposive social action that were not intended by the actors—and may not serve any coherent function at all beyond the fact that they occurred.

Modern coordination breakdown contains both.

Platforms and modern institutions did not set out to dissolve closure, cheapen commitment, or convert time into ambiguity. They set out to increase access, efficiency, expression, and optionality. Those are purposive goals. Yet the cumulative effect has been the systematic weakening of binding.

That weakening is not best understood as malice.

It is best understood as an unanticipated consequence of systems designed to maximize freedom of movement while minimizing consequence of exit.

This is one of those sociological ironies that does not announce itself as irony at the time. It arrives only later, as fatigue.

Binding is the mechanism by which present speech constrains future action.

It is the difference between an intention and an obligation. It is what converts words from expressive artifacts into stabilizers of expectation. Where binding functions, time passing changes state. Silence becomes legible. Exit becomes explicit. Commitment narrows options. Refusal closes.

Where binding fails, none of these functions operate reliably:

- time passes without consequence

- silence becomes interpretive material

- exit becomes drift

- closure becomes optional

- commitment becomes a mood

- responsibility becomes negotiable

The system does not become more humane. It becomes less legible.

Actors are forced to infer intent because intent no longer binds itself.

This generates the characteristic condition of late-modern interaction: continuous engagement without settlement.

We may therefore distinguish, in the contemporary setting, not merely between those who accept or reject goals and means, but between those who bind and those who signal—between actors who permit time to close action, and actors who preserve optionality by keeping meaning reversible.

That distinction, rather than temperament, accounts for much of what is now misdescribed as “miscommunication.”

When a system ceases to bind, the individual is compelled to compensate. The mind begins performing tasks that stable structures once performed automatically: interpreting delay, reading tone, assigning meaning to silence, forecasting future intent from present signals.

This produces vigilance.

Vigilance is costly. It requires sustained attention without resolution. It maintains arousal without closure. Hence exhaustion becomes the modal affect—not heartbreak, not rage, but fatigue.

Moreover, this burden is unevenly distributed.

Those who attempt to coordinate—to propose, to clarify, to close loops—bear immediate cost. Those who preserve optionality conserve energy. The system thereby selects for cost externalization without requiring malice. One can be sincere and still behave in structurally extractive ways because the environment permits sincerity without settlement.

The moral drama is a distraction. The mechanism is pricing.

The modern world has replaced shared guarantees with individual optimization, and then blamed individuals when optimization fails.

This shift is visible in finance, in labor markets, in institutional trust, and in interpersonal life. When enforcement collapses, the system does not become freer in any stable sense. It becomes more demanding of private regulation—more interpretation, more vigilance, more cognitive expenditure.

Durkheim named the condition: anomie.

Merton formalized adaptive outcomes: strain theory.

What I am naming is the contemporary central mechanism:

Binding Failure → Coordination Collapse → Optimization Regime → Trust becomes local and fragile.

That mechanism explains why communication can intensify without producing stability; why sincerity can remain widespread without coordinating behavior; why norms can proliferate while outcomes drift; why good-faith participation can become exhausting rather than rewarding.

One may respond to this condition morally, therapeutically, nostalgically, or politically. Those responses may be consoling. They do not address the structure.

Anomics does.

It proceeds from the premise that where norms cease to bind, coordination will fail—even in the presence of sincerity—and that the resulting failures will not appear as sudden collapse, but as chronic exhaustion, diffuse resentment, and persistent inability to close.

This is not a claim about bad people.

It is a claim about the operating system under which modern life now runs.

And like most operating systems, it does not fail by exploding. It fails by producing exactly what it was built to produce, only faster than anyone expected.